During this weeks investigation of Music in 21st Century Education I was presented with a challenging question. This question looked into how we as music educators approach our students, how we inevitably build on the experiences we had as students and how we integrate within the musical culture our students are now a part of.

“How important is the teaching of your students’ own musical culture, against teaching traditional music skills, literacy, and western art music?”

If I was to address this I needed to reflect on three things:

1. How I was taught about music.

2. How I was taught what music education should look like.

3. What I think music education should look like now.

Inevitably the research presented showed the changing paradigm in our students musical culture revolving around electronic music, improvisation and social music making. Dr Lucy Green, Professor of Music Education at London Global University (UCL), was intrigued with how ‘popular musicians initially learnt their craft’ (paraphrased). Could this be applied to the music classroom and what benefits would it have on our students learning music? Coming from a similar musical background I found her research into how ‘popular musicians learn’ intriguing.

In my own musical training I started with classical guitar at the age of five. But quickly gave up. I took up playing the guitar again, in high-school, this time to play the music I wanted to play. That is, the music of DireStraits, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix and Tommy Emmanuel. It was only because of my classroom music teacher throughout secondary school that I remained focussed and engaged in learning ‘other’ musics. My classroom teacher, David Stonestreet, taught us about classical music but also musicals, rock, and music technology. It was in these classes that I found a love for recording, midi orchestration and sampling. I was engaged and found ways to link the other styles of music taught by Mr Stonestreet, into my own playing and composing. In some ways I learnt the way Dr Lucy Green’s research outlines above.

There is now a complete approach called The Ear Playing Project, based on Dr Green’s findings that “…focuses on one of the central ways in which popular musicians first acquire their skills – that is, listening to a recording, picking out a part, and attempting to play it by ear, usually with little or no formal guidance.” But is this what is needed in our schools with assignments and grades? Does it give a complete picture for music education?

I find Dr Green’s approach could be built into the teaching of necessary skills and content. But I wanted to take this reflection further. If Dr Green’s research resonated as true, what should music education look like? In an article entitled “Sound before Symbol: Lessons from History” the pianist Andor Földes is quoted as saying:

“There is no such thing as a proper age for a child to start playing the piano. I avoid saying ‘to start his musical education’ because I believe that an education in music should start very early, perhaps years before the child ever actually learns how to read notes, or can find his way among the black and white keys.”

‘Keys to the Keyboard’ 1950.

The above quote implies that even from the earliest age, experiential music learning needs to occur. I would argue not just working out a part on an instrument from music we like, but experiencing music in such a way that we can play and listen to any type of music with understanding.

Being trained in the Orff Approach this also fits with my philosophy of music education. It needs to find ways of supporting student centred inquiry (termed elsewhere, scratching their own itch), but also incorporating a framework that helps them learn, opening new paths and building their skills. Essentially taking Dr Green’s research, adding scaffolding, and developing the skills, literacy and content through musical experiences.

In the video below Richard Gill AOM gives a music masterclass where students can be seen engaging with all manner of activities that are inherently musical. Mr Gill personifies ‘Sound before Symbol.’ Also, being aware of the Orff Approach, I am confident that a lesson like this can be utilised in any classroom or year group.

I have been a music teacher of Kindergarten through to Year 12. Lessons like the one above work with both elementary and secondary students depending on how you decide to use the implied scaffolding. Additionally, students are engaged and learning about music while playing and listening. In their article “When Kids Have Structure for Thinking, Better Learning Emerges” Mindshift argue that when “…teachers make thinking visible, [they are] very effective at helping students dive below surface level retention of information into really understanding material as it connects to the rest of their studies and their lives.” [emphasis mine]

This is how I envision music education today. I could take Mr Gill’s lesson above and use it to teach Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition or how to compose like Flume with Ableton Live (video below). Can you see how Mr Gill’s lesson could lead into a performance, composition or even musicology class? His class are internalising rhythm, pitch and texture while they move and play – this is good pedagogy.

In summary, we do need to engage with our students’ own musical cultures. We also need to encourage them to learn from the music they identify with – but we as educators are also required to teach skills, content and musical literacy. This doesn’t need to be an either-or-argument, instead I believe with the Orff Approach, strong scaffolding and the combination of all musical styles, music education in the 21st Century could adapt and provide more powerful ways of learning.

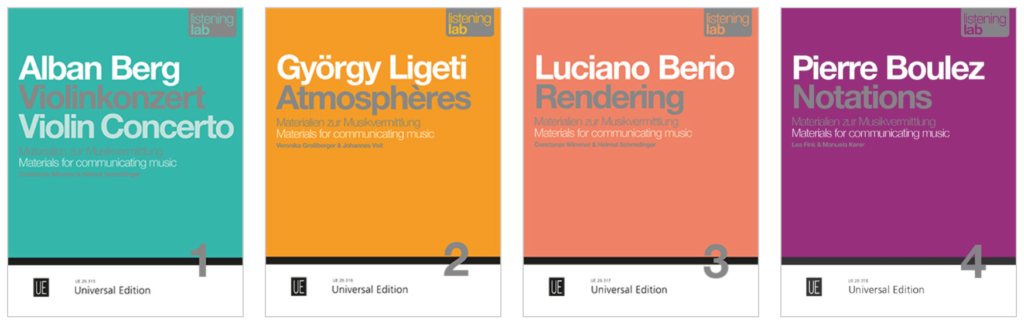

To see what this would look like in a more extensive setting I highly recommend the following books from Universal Edition Listening Labs. The videos demonstrate various musical experiences that build on sound pedagogy as students study 20th Century Art Music.

Photo Credit: BarnImages.com

I agree that making musical thinking visible is very important no matter the content. Going from where the students are at is also important. I have been playing around with getting the students to share their musical thinking by getting them to use the think aloud protocol and it has, in turn helped me shape my teaching.

What I am trying to say is that beside content, what is magical is when there is interdependent engagement between teacher and learner.

Great article. It resonated perfectly with my thoughts on using commercial music to engage and connect with students. Even more so, using Local music, that even if they don’t already connect with it, the mere fact it is a guy/girl that could have been from their local high school makes it wonderful for students. Funny you used Flume’s song here, I used it in a workshop a few weeks ago, the kids loved dissecting it, and when I told them Flume was an Australian boy, they were even more engaged, some didn’t even believe he was AUSTRALIAN.

Would love to discuss some ideas. If you are open to it please email me.

Phil

I agree Betty! Thanks for your insights. Having that moment where teacher and student have ‘musical engagement’ on a project, or in a discussion is what I live for.

You are welcome Phil. Thanks for commenting and yes, I enjoy Flume’s music very much. I did some studies at Ableton Liveschool in Australia where he also has taught. In fact you and your students can go through Ableton training for free based upon some of his hit tracks here: https://liveschool.net/free-ableton-live-course-with-flume/

I just emailed you and lets work on something together. I’ve got my students at my new school developing projects along similar lines.

Pingback: Wright-Stuff Music » Music in 21st Century Education – Week 5